I've been writing and speaking and workshopping a lot about Money Stories (here, here, here): the very simple numerical descriptions of how various products or features or projects will make money for our company – rather than details of the tech involved. Money Stories are very handy for framing individual trade-offs between vaguely similar things: one in-demand customer features versus another; an "out of the blue" special widget to close an enterprise prospect versus major revenue-driving roadmap items; various operational improvements for the same internal user base.

But I haven't found them as useful in the biggest CPO battle: protecting a major slice of R&D to keep our current products working and our technical infrastructure solid. This is what I've been calling care & feeding*: bug fixes, incremental features, scalability, small UX improvements, algorithm tweaking, refactoring, development tools, automated test infrastructure, design patterns, architecture, maker team training… all of the work that lets us stay in the software business from year to year.

Almost every week, there's some looming trade-off between ongoing care & feeding and some new short-term revenue opportunity. Here's my observation: when presented with a choice between revenue this quarter and unsexy-but-essential investments in products and tech, I expect go-to-market execs to pick the immediate revenue bump 95% of the time. So as product and engineering leaders, we are doing them a disservice by giving the impression that debating ticket-level priorities leads to sustainable products or consistent revenue or healthy companies or productive engineering teams.

Instead, I see this as a portfolio problem. At the company level, we need to agree on a portion of R&D's overall effort that will go toward care & feeding: keeping our products healthy, and customer-pleasing, and earning their long-term keep. In my experience, we can't expect go-to-market-side execs or stakeholders to understand and deeply appreciate the nuances of subtle product/technical trade-offs. Just as they can't expect maker teams to help choose sales methodologies (Challenger vs SPIN vs solution selling) or recommend accounting tax treatments (details of what qualifies as CapEx) or out-wordsmith the growth marketing team's social influencer posts. At the most senior level, we have to trust each other to run our organizations for the good of the business.

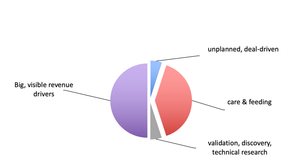

But every executive understands investment portfolios, so I start there. Similar to retirement portfolios which split funds across a set of financial asset categories (stocks, bonds, real estate, crypto…), our R&D budget needs to be allocated across a few broad categories:

- Big, visible revenue drivers: strategic customer-demanded features, upsell opportunities, revenue-focused packaging and price tiers, planned strategic features, major visible UX improvements. Awe-inspiring AI insights. In effect, the very long list of things that customers ask for by name, that our marketers celebrate, that our sales teams pitch and demonstrate, that our CFO talks about in quarterly investor briefings. These are the things that obviously convert into money. These are the money stories we need to create and prioritize.

- Care & Feeding: architecture, quality, incremental improvements, instrumentation, scalability, security, design systems and less visible UX work, test automation, code management and developer tools, application instrumentation, DevOps, ProdOps. This is the very long list of things that we must do to thrive in the software business. The work that keeps our apps running smoothly, that reduces incoming support issues, and that lets our very expensive teams of brilliant makers do their jobs. Individually, care & feeding work is hard to match against specific cost savings or efficiency metrics, but is essential to keeping working systems working.

- Validation, discovery, technical research: This is the small but critical slice of product work, supported by engineers and designers, to increase our chances of shipping things that truly matter in the marketplace – and eventually encourage customers to pay us money. End customer interviews, usability testing, competitor analysis, customer journey mapping/Jobs To Be Done, user forums and advisory boards, external stimuli. The fuzzy front end of innovation and user/buyer/marketing insight. It's extremely difficult to tie specific discovery activities to specific revenue or savings, since we don't yet know what we don't yet know… so discovery is the first thing to be tossed overboard for some major account sweetener.

- Unplanned and deal-driven: Especially in B2B/enterprise companies, these are the insertions and surprises that blow up our roadmaps and torpedo our commitments. Usually they are tied to last-minute demands from major prospects, weighted with dire consequence. ("Volkswagen says they won't renew our €8M contract if we don't add teleportation to the product by Friday.") Escalations to the CEO follow immediately, and this repeatedly undercuts our planned work. And destroys the enthusiasm of our maker teams.

Framing the overall R&D budget (or effort or time-spent) as a high-level portfolio lets us ask better questions and make better choices. And helps frame trade-offs among like items: “here are the 3 major revenue drivers we’ve agreed on. Which of them do you think we should cancel, and replace with this new revenue opportunity?” Notice that we’ve tried to exclude borrowing from care & feeding as our default revenue answer.

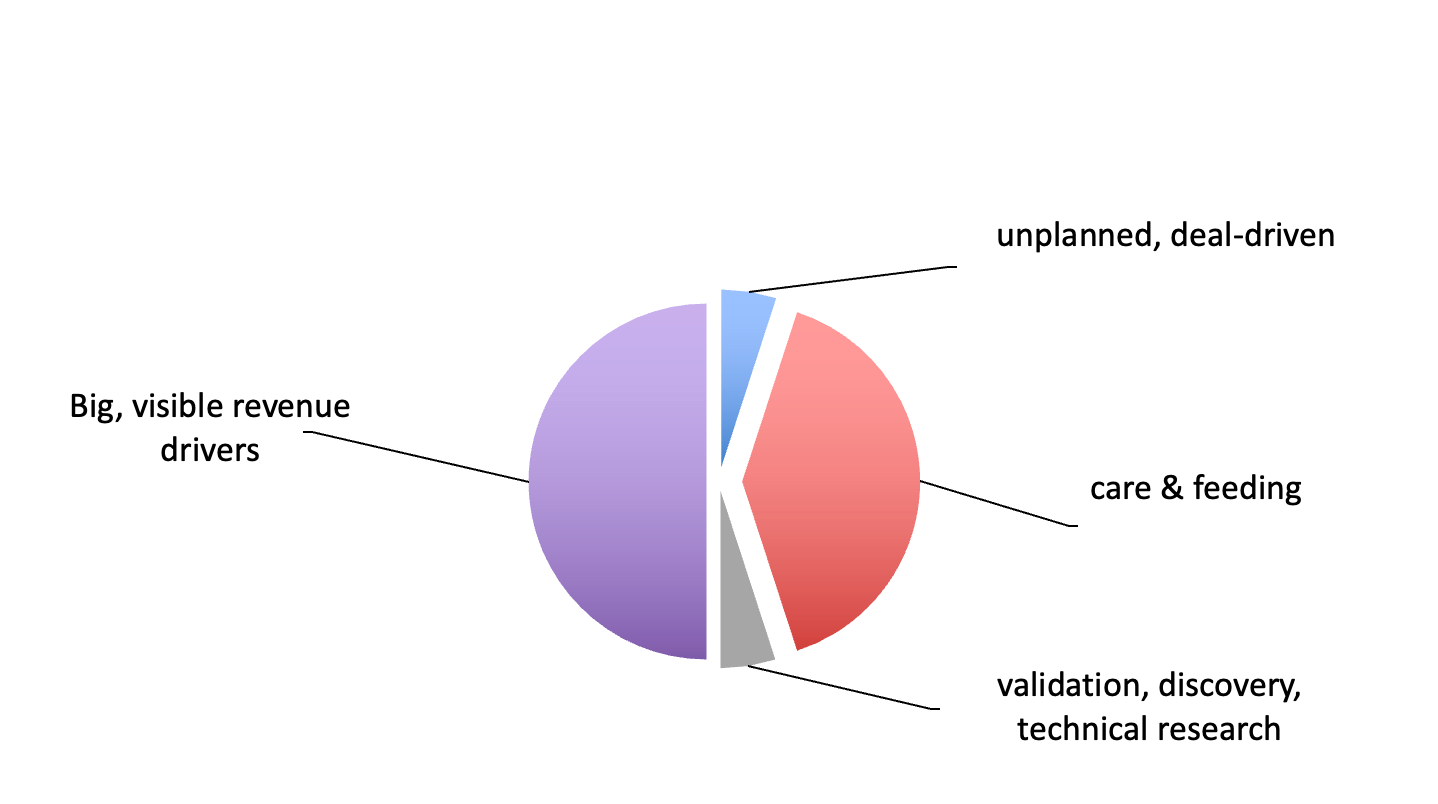

There is no magic universal allocation among these four categories. "It depends," as every product manager says too often. But for companies that have already found product/market fit and are not yet ready to de-invest or harvest, I usually start with 50% customer-visible revenue drivers, 35-40% care & feeding, and 5-10% discovery. When unplanned or deal-driven work wanders above 10%, I worry that the R&D function is drifting toward a professional services model and one-time project work for individual customers. (That's a fine business model, but is fundamentally at odds with a build-once-sell-many product model. See my Second Law of Software Economics. Which is why pure SaaS companies typically have P/E ratios 3x to 10x higher than tech consulting and outsourcing firms.)

Rich's Starter R&D Portfolio Mix

for Software Product Companies

● 50% big, visible revenue drivers

● 35-40% care & feeding, technical

investments, existing features

● 5-10% discovery

● 5% unplanned/deal-driven

Worth noting that the numbers should total to 100%. 🙂 I’ve had leadership teams happily share allocations that total 120% or 140%, not seeing their failure to make hard choices. And I know some enterprise sales teams that aren't happy unless all of R&D is allocated to deal-specific work.

In my coaching and workshops, I ask participants to rough-allocate their last quarter's R&D spending into those four categories (aka portfolio pie slices). There are no perfect or canonical answers, of course, but we usually uncover some very striking imbalances:

- Organizations putting 65%+ effort into shiny new features, and 20% or less into maintaining what's already deployed (and which customers are paying hefty support fees to keep healthy). Their products tend to be feature-heavy, architecture-poor, badly curated, with declining quality/resilience/usability, and in perpetual engineering crises as things break and custom commitments pile up.

They are often using “one and done” project funding models, where the entire team is moved to something else once v1.0 ships. First releases are always missing items: obvious small improvements, high-priority bugs, and learnings that would go into v1.1 in an ongoing product funding model. So the company has a vast collection of underwhelming products and broken toys. - Groups spending 60%+ on technical work, maintenance, replatforming, quality. This is usually the boomerang result of years of neglect and under-investment in healthy tech. The CTO stops most new development, which can only last for a few quarters.

- Organizations putting 25%+ effort into projects for individual customers, with the illusory hope that the results will be instantly and broadly sharable. These are really professional services companies… renting out their engineers to specific corporations, talking about productizing one-off work but then inevitably borrowing that tiny productization team to shore up another engagement. (Over and over again.)

- It's rare to see more than 10% in discovery activities -- sometimes at pre-revenue or pre-shipment companies, where we're still understanding product/market fit. Discovery is usually the first category to be sacrificed when schedules get tight and commitments are late. (Hint: schedules are always tight and commitments are always late. Product and Engineering leaders can't afford to postpone discovery until the smoke clears.)

It's much more productive to have a strategic portfolio-level argument about R&D resources and focus, rather than dragging executives through a 900-row spreadsheet or deep-tech choices. Engineering and Design and Product are better equipped to make thoughtful trade-offs within an overall "tech" budget. Which should give our go-to-market partners fewer things to worry about.

But at many organizations, setting up this effort allocation at the beginning of the quarter doesn't keep company leadership from asking for just-this-once-and-never-again shifts from committed roadmap work to of-the-moment opportunities. (Hint: just-this-once happens every week. I've seen endless examples of "commitment amnesia" where the C-suite forgets yesterday's ironclad strategic agreement by tomorrow – when the next big customer asks for the next big thing.) So I encourage CPOs and CTOs to keep a list handy with specific items that we'd have to forgo to add just-this-one-more-small-thing into an already overcommitted roadmap:

- Outages: "Remember when our X went offline, customers buried you in complaints, and we lost Y accounts? That's why we need to keep working on this set of DevOps things."

- Scalability: "We're near 90% capacity in our report generating processes. The company wants to grow 25% next year, and we won't be able to add those users without major improvements to the reporting engine."

- UX/design research: "Remember that improvement we made last quarter to our sign-up flow… that boosted conversation rates by 2% and put $8M extra on the top line? That's why our designer spent so much time observing real users and experimenting with alternate flows. We hope to find something similar this quarter."

- Security: "Remember when our top competitor Z got hacked, they lost data on 10M users, and the CIO lost his job? That's why we're doing A and B to keep that from happening here."

- End-of-support: "remember when we dropped support for the 2013 codeline? That freed up 7 people to work on revenue projects, which is why we want to sunset the 2014 and 2015 versions – put our energy where it matters. But that requires product management and support work to transition those legacy customers forward. And sales-side executives to say ABSOLUTELY NOT when customers with these old versions want us to extend our support dates."

- Test frameworks. "Manual testing is slow, expensive, and error prone. We're now at 32% coverage for automated testing… every incremental 2% saves us $500k in outside manual testing and improves quality and speeds up the development cycle. We can boost quality while saving money, but only if we don't borrow that group for a different project."

In case you missed the pattern above, these are all money stories about critical infrastructure work, wrapped in painful experiences or downside business risk. I find that most go-to-market-side execs don't retain the instances or rationale for care & feeding or technical investments. Their attention and expertise are appropriately focused elsewhere, and they are rewarded for current quarter revenue. (That's not a criticism, but an observation about how we pay and reward them: "Close the major deal, and move on.") So product and engineering leaders have to repeat these reminders – often – which means keeping our lists handy and translated into business outcomes.

Sound Byte

It's really hard to sell care & feeding work to executives who are richly rewarded for current-quarter revenue. IMO, selling these at the ticket or project level is a job for Sisyphus. So as product-side leaders, we need to negotiate a sensible slice of the R&D budget to keep the business in business. (I believe that 35% is the minimum to keep most tech companies viable.) That means uncomfortable portfolio-level trade-offs rather than uncomfortable detailed-feature-and-fix-level trade-offs.

* There are lots of alternate names for Care & Feeding: Business As Usual (BAU), Keep The Lights On (KTLO), architectural initiatives, technical work, maintenance, ongoing support. I don't love any of these, including my own. My big concern is that they trivialize critical work or suggest that it's optional. BAU, especially, may give the impression that we're boring our audience and not thinking creatively. Maintenance sounds like unskilled work. I suggest trying out various labels to identify which communicate real value and real urgency to your executive team.